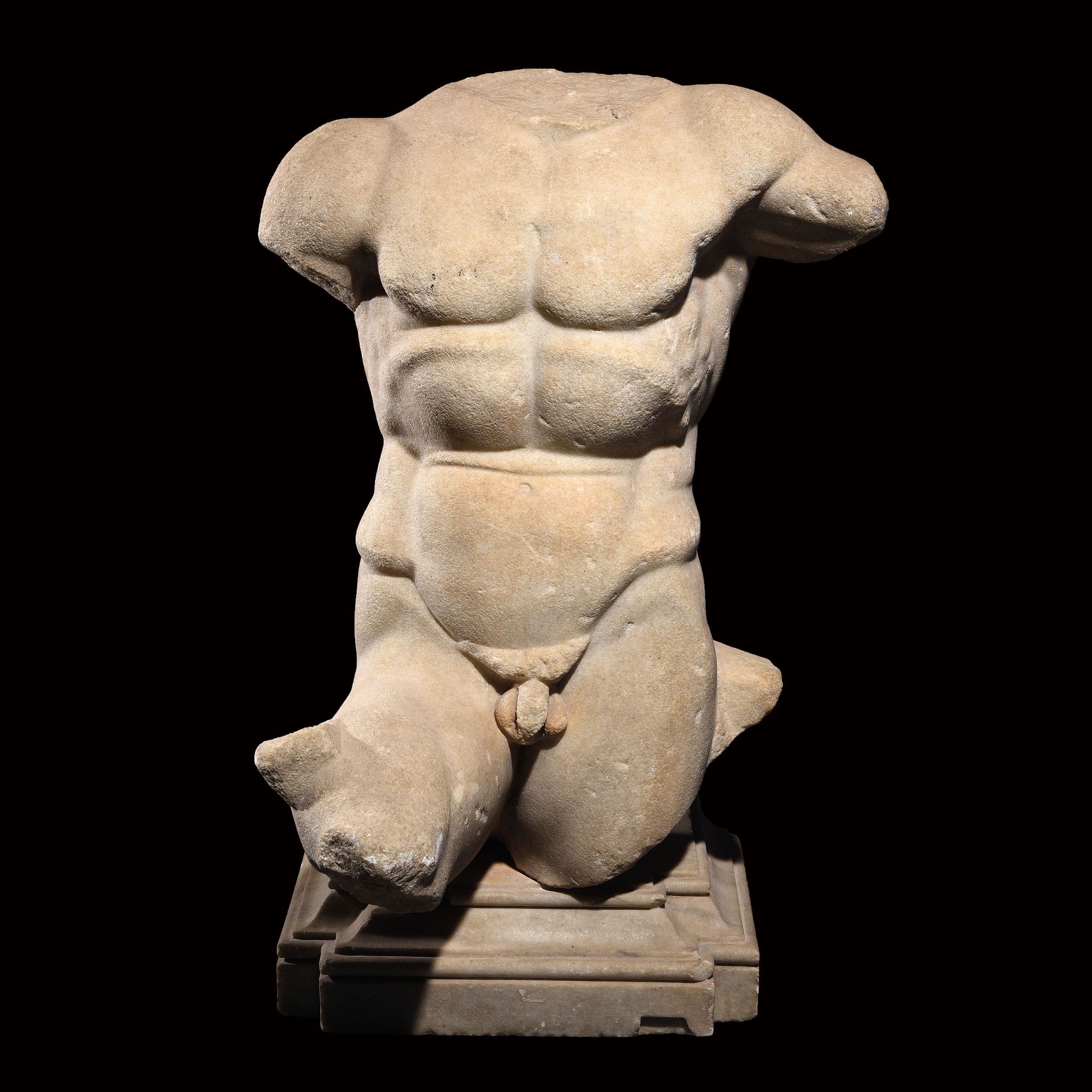

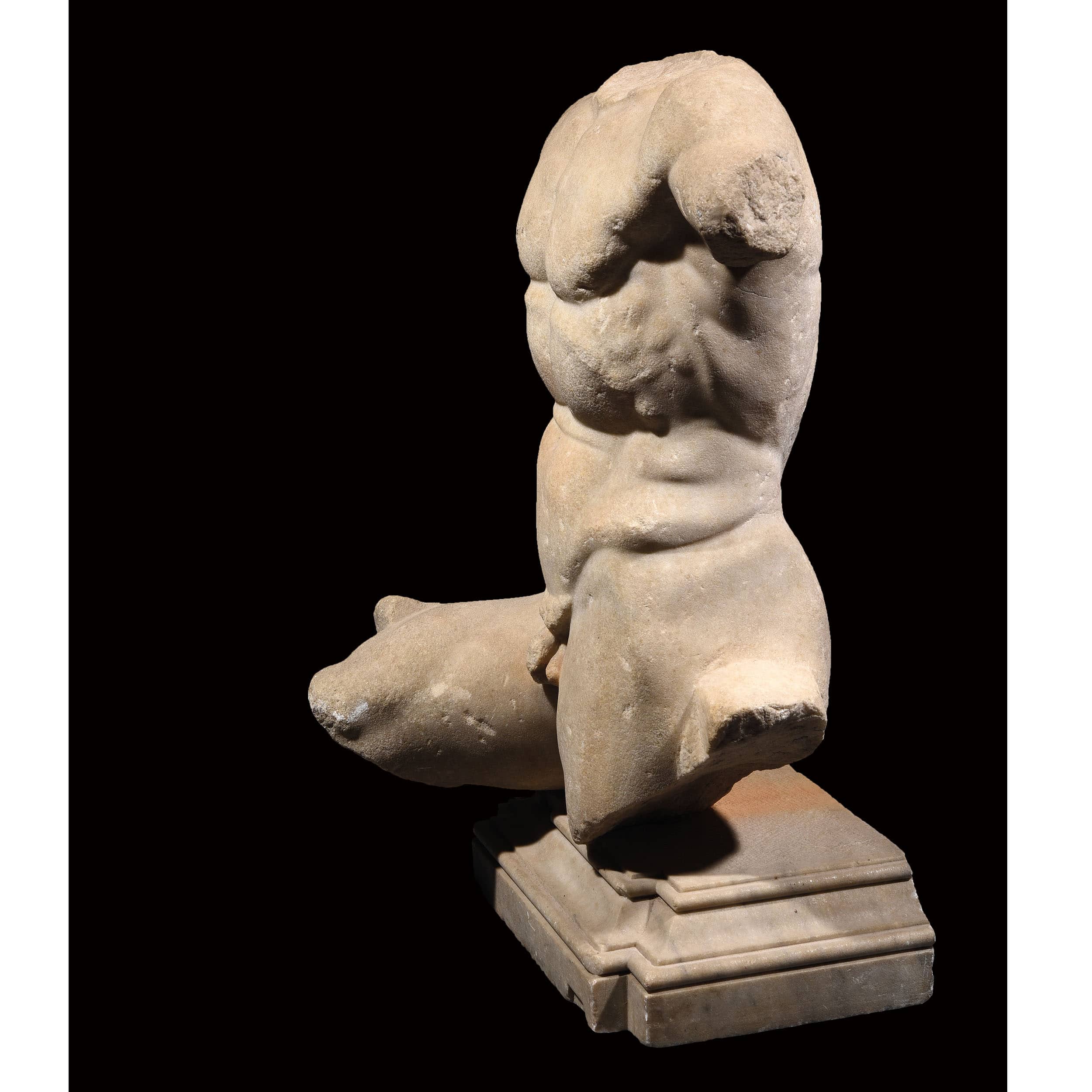

Art romain, Ier siècle

Marbre ; Dim_61 x 46 x 38 cm

Provenance

Ancienne collection privée suisse, vendue à la galerie Koeller

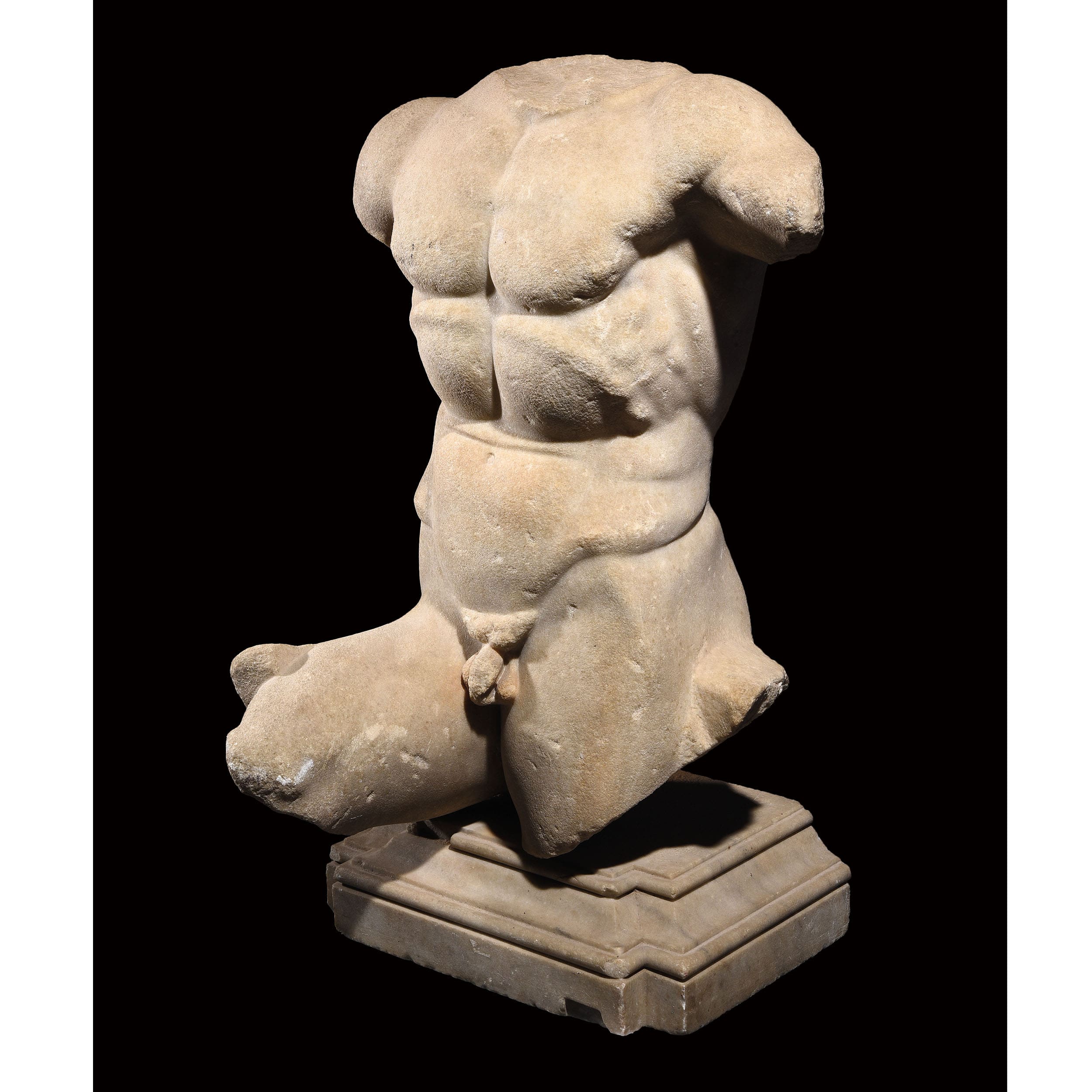

A ROMAN MARBLE HEROIC TORSO 1ST CENTURY A.D. 24 x 18 x 15 in. Torso of a statue representing a man

standing in a posture that exalts his powerfully developed muscles. The hollowed out stomach, the deep lines

of the abdomen as well as the prominent ribs indicate the figure had the upper part of the body tilted forward.

The stay on his right thigh confirms this hypothesis, suggesting a forward action of the right arm. The right

thigh, parallel to the ground, indicates that the leg was bent at the knee and rested on a structure (base of a column,

rock ...). The left thigh, on the other hand, perpendicular to the ground, indicates that it is the supporting

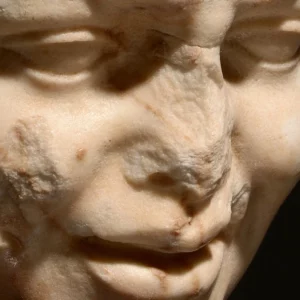

leg. The highly detailed anatomy - a powerful rib cage, angular and protruding pecs, a very pronounced Apollo

belt - as well as the movement of the body, refer to representations of certain heroes, generals or emperors in

heroic nudity. One thinks in particular of the group “Liberation of Prometheus by Heracles” kept at the Berlin

Staatliche Museum, inv. AVP VII 168 and dated between the end of the 2nd century and the beginning of the 1st

century BC (fig. 1). The myth, known from Hesiod (Theogony 507-616), of Prometheus, forged on a rock and

tormented by an eagle, which is freed by Heracles, found its pictorial representation with this group in Hellenism

and kept it as model until late in the Roman Empire (cf. sarcophagus in Rome, Musei Capitolini, inv. 329

(fig.2)). Or the statue of Caius Cartilius Poplicola (fig. 3) in Heracles; that of General Pompey in Neptune from

the Opperman1 collection, and more generally representations of deities - statues of Neptune of Elefsina (fig.

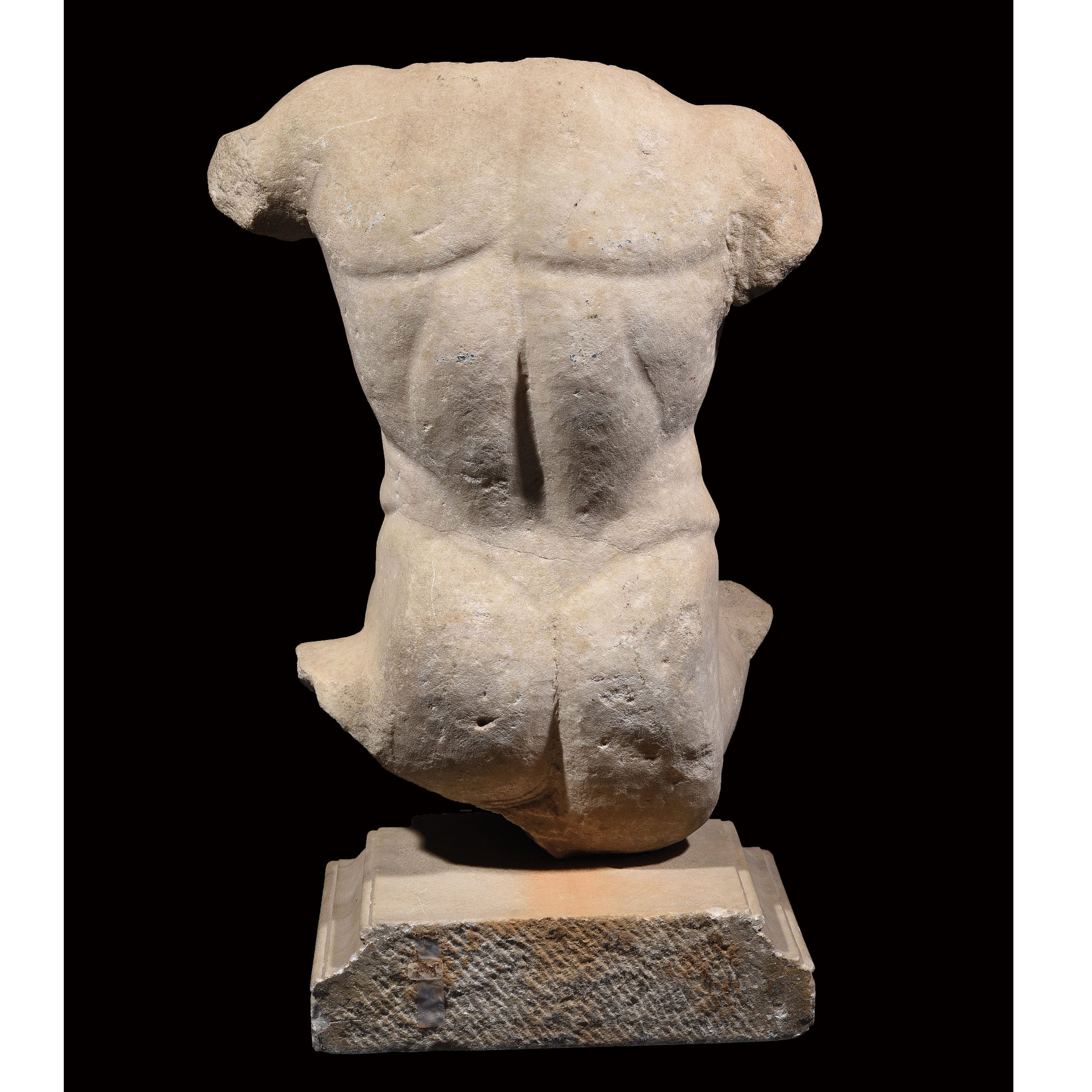

4) and of Athens (fig. 5). Finally, the back of the sculpture, less defined, allows us to suggest that this statue

should be positioned in a niche or be part of the decorum of a large architectural ensemble.

Torse de statue représentant un homme debout dans une posture qui exalte sa musculature puissamment développée. L’estomac creusé, les lignes profondes de l’abdomen ainsi que les cotes saillantes indique le personnage avait la partie haute du corps penchée vers l’avant.

L’étai présent sur sa cuisse droite confirme cette hypothèse, suggérant une action du bras droit vers l’avant. La cuisse droite, parallèle au sol, indique que la jambe était pliée au niveau du genou et reposait sur une structure (base de colonne, rocher...). La cuisse gauche quant à elle, bien perpendiculaire au sol, indique qu’il s’agit de la jambe d’appui.

L’anatomie très détaillée – une puissante cage thoracique, des pectoraux anguleux et saillants, une ceinture d’Apollon très prononcée – ainsi que le mouvement du corps, renvoient aux représentations de certains héros, de généraux ou d’empereurs en nudité héroïque.

On pense notamment au groupe de «Libération de Prométhée par Héraclès» conservé au Musée de Berlin Staatliche, inv. AVP VII 168 et daté entre la fin du IIème et le début du Ier siècle avant notre ère (fig.1).

Le mythe, connu depuis Hésiode (Théogonie 507-616), de Prométhée, forgé sur un rocher et tourmenté par un aigle, qui est libéré par Héraclès, a trouvé sa représentation picturale avec ce groupe dans l’hellénisme et l’a gardé comme modèle jusque tard dans l’Empire romain (cf. sarcophage à Rome, Musei Capitolini, inv. 329 (fig.2)).

Ou encore à la statue de Caius Cartilius Poplicola (fig.3) en Héraclès; celle du général Pompée en Neptune (fig.4) de la collection Opperman(1), et plus généralement des représentations de divinités – statues de Neptune d’Elefsina (fig.5) et d’Athènes (fig.6).

Enfin, le dos de la sculpture, moins défini nous permet de suggérer que cette statue devait être positionnée dans une niche ou faire partie du décorum d’un grand ensemble architectural.

1 E. Babelon, Catalogue des bronzes antiques de la Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, 1895, n.830

Description complète